SHARE

The Glaring Need in Social Determinants of Health

Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.3

In general, SDOH factors may include access to healthcare services, medications, job opportunities, food, housing, income security, social support, and others.4

Those living with epilepsy are significantly impacted by SDOH because of the general misunderstanding and burden of their condition2

These patients deserve more visibility into the factors that limit their health and more ways to get the care they need. We are committed to leading that long-awaited change, and it starts with observing these needs in care disparities:

Click on each care disparity on the brain below to find out more about how they impact outcomes.

Racial & Ethnic Inequalities

- Epilepsy is more common among minorities5

- Minorities have more limited access to healthcare and tend to receive a lower quality of care5

Surgery & Emergency

Room Visits

African Americans and Hispanics have:

Higher rates of hospitalizations and emergency room visits5

Lower rates of undergoing surgery (African Americans are

60% less likely)6

ONLY

2.4-5.9% of African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Native American patients had temporal surgery compared to

6.5% of White patients6

Access to Specialists

Only 9% of African American patients

and 24% of Hispanic patients

have access to an epilepsy specialist

compared to 57% of White patients6

African Americans:

Are 30% LESS LIKELY to see an outpatient neurologist5

LGBTQIA+ Discrimination

![]()

Health insurance, employment, housing, and social program access is limited due to legal discrimination7

![]()

Limited research to support the effect of epilepsy medications on gender-affirming hormonal treatments8

~50% of clinicians recognize sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) as SDOH8

![]()

Shortage of healthcare providers who are knowledgeable and culturally competent in LGBTQIA+ health is a problem7

Over 40% feel SOGI shouldn’t be considered for neurological disease management8

Employment Opportunities

People with epilepsy have

56% lower odds of employment

miss 3x as many work days

and earn approximately

50% less in annual wages

compared to those without epilepsy9

32% of adults with epilepsy

are unable to work

vs 7% without epilepsy10

Epilepsy vocational rehabilitation programs are very few, and access to work remains an obstacle for those with epilepsy11

Stats on the Treatment Gap

In the US:

~50%

of newly diagnosed epilepsy patients don’t receive treatment

until 1 year after diagnosis12

37%

of newly diagnosed epilepsy patients remain untreated

at 3 years from diagnosis12

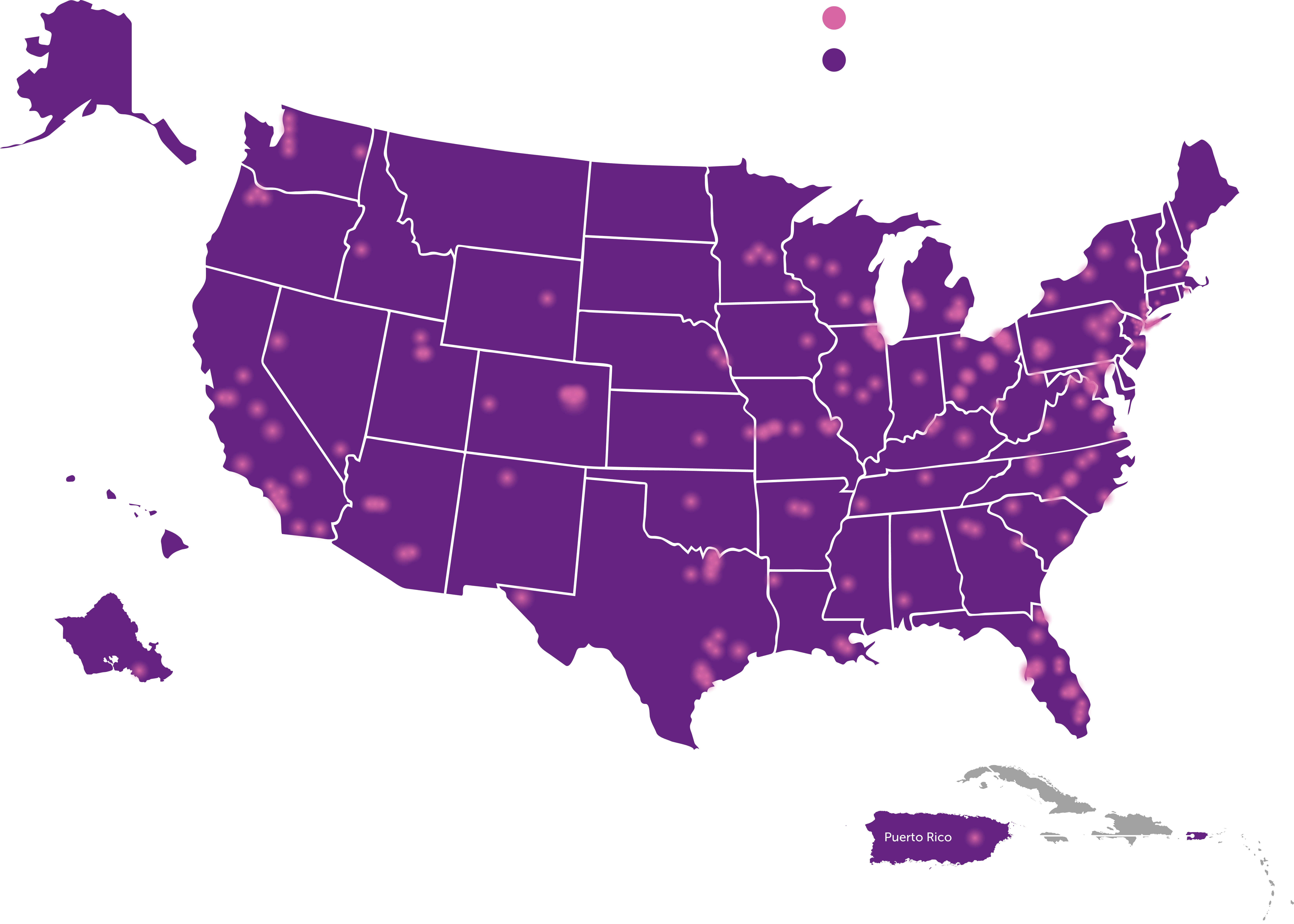

Geographical Barriers

Quality of care, pricing, and epilepsy specialist availability vary widely by geographic area. In rural locations, access to specialists is especially restricted, making location key in receiving adequate health care5

The map below shows epilepsy centers across the US. Notice the lack of epilepsy centers in the more rural states13

Poverty & Financial Challenges

~8x

greater rate of epilepsy

and seizures in the

homeless population14

30%

of those with active

epilepsy live in poverty5

4 in 10

children with epilepsy

live in homes at or close

to poverty level15

3 in 10

children with epilepsy

live in homes without

enough food15

Food insecurity is associated with mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression, especially among low-income populations16

16%

of those with active

epilepsy are uninsured 17

7/10

patients without

insurance have a

significantly lower

likelihood of seeing

an epilepsy specialist5

Poverty restricts opportunities for quality care and treatment for epilepsy, leading to worse health outcomes5

People living in poverty are less likely to use medications and are more associated with nonadherence5

You + Us = Improved Population Health

Health equity needs priority. Measures to reduce disparities need action. And filling these gaps in care can be a reality when you work with us. Training physicians, nurses, and other healthcare workers on the social determinants of health is a tangible step to promote more equitable health outcomes. Let’s start broadening awareness of SDOH in epilepsy not only today, but every day.

Join our SDOH efforts by meeting with a UCB representative

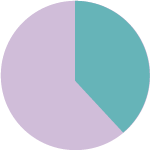

Clinical care is only one factor impacting health outcomes

About half of an individual's outcome is comprised of socioeconomic factors and physical environment — meaning factors outside of healthcare delivery impact patient quality and length of life19

Estimated proportion of factors that influence health outcomes

40%

Social and economic factors

30%

Health behaviors

20%

Clinical care

10%

Physical environment

Examination of mediating pathways through which SDOH influences epilepsy outcomes is needed to bring meaningful change.1 These pathways include:

Living and working conditions

Patient behaviors

Self-care

Healthcare access

Addressing these SDOH factors and pathways may improve access to care and population health outcomes, helping to fulfill health equity goals along the way.

Do you know how SDOH may be affecting your epilepsy patient populations?

Quintuple Aim:

UCB’s Way of Inspiring Change

The Quintuple Aim model serves as our foundation for shifting the focus from point-of-care health to optimizing overall health for populations.20

Select 1 of the 5 key areas of focus to see how it addresses social determinants of health in those with epilepsy.

The Quintuple Aim sets the stage for identifying patients with epilepsy who have suboptimal health outcomes due to disparities in care. At UCB, we continuously update our goals by listening to the needs of patients and care teams to move epilepsy care forward.

Patient Insights

5 Foundational Insights of Living With Epilepsy

The Hope and Trust studies were 2 qualitative research studies conducted by UCB to gain a deep understanding of what it’s like living with epilepsy.

- “HOPE” included 152 patients who have been successfully diagnosed and treated and are able to manage most of their symptoms with available therapies*

- “TRUST” included 12 patients whose epilepsy didn’t respond to treatment, for whom seizures are an ever-present risk, and for whom coping constitutes a significant portion of their lives†

In each case, the researchers were able to document numerous ways, beyond the obvious threat of having a seizure, that epilepsy was taking value from these patients’ lives and keeping them from their full health potential.

The results were distilled down into 5 insights21:

- 1 Stigma Is a Force: Even the most controlled epilepsy sufferers say that they feel isolated. Their seizures, fear of seizures, time spent in medical care, and the need for daily medication all mark them as epilepsy sufferers and different from those around them.

- 2 The System Is Not Built for Me: From diagnosis forward, patients struggle to navigate a system that is confusing and that feels designed to deny the care they need—but getting off to the right start is critically related to overall success.

- 3 Life in Between: A surprising number of epilepsy patients say that they spend too much of their lives waiting. They wait for appointments, prescriptions, titration, response, access issues, and especially for achieving “control.”

- 4 Complexity of Control: While patients and physicians both use the term “control” to describe their goal for therapy, the term differs, depending on who you ask. For most physicians, control is about counting seizures, while for those with epilepsy, control means emotional and social stability.

- 5 My Epilepsy, My Journey: Each of them is on their own unique journey with unique experiences and challenges. There is no “epilepsy,” only multiple different “epilepsies,” and there is no single medicine or care strategy that will provide the ideal solution for every patient.

*The study also included 28 caregivers and 32 physicians.

†The study also included 18 caregivers.

When it comes to creating patient value in epilepsy, the challenges have never been greater. At UCB, our mission in epilepsy is to achieve individualized solutions for individual needs to help bring patients their ideal outcome.

To support our mission, we’ve developed a tailored information hub for patients and populations in need of epilepsy education. Share this content with your patients to start constructive conversations.

The economic costs of epilepsy are broad

Epilepsy isn’t only a burden on people, it’s a burden on our entire healthcare system—especially when it’s uncontrolled or misdiagnosed. UCB is dedicated to help alleviate the immense impact epilepsy has on hospitals and care teams, and it starts with knowing the facts.

~$28 billion

in estimated annual US epilepsy-related costs22*

Epilepsy-specific costs are 2.2x higher for uncontrolled epilepsy vs stable epilepsy22†‡

Patients with uncontrolled vs well-controlled epilepsy have:

5x

higher rate

of ED visits and

inpatient stays22§

2.2x

higher risk

of epilepsy-related

hospitalizations23

7x

longer

hospital stays22

>$7K

epilepsy-related healthcare resource utilization costs (PPPY)22§

Hospital encounters alone inflate the cost of epilepsy:

Nearly

1.4

million hospital stays linked to

diagnosis of seizures22

~$1.8

billion

in hospital costs22

~65%

of ED visits

result in hospitalization22

* Estimate is based on a reported cost of $26 billion in 2013 converted to 2018 dollar value.22

† Retrospective claims study conducted between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2009, with MarketScan commercial database representing all major regions of the United States.22

‡ Uncontrolled: Added seizure medication to an existing regimen during year of observation; Stable: No change in seizure medication for at least 1 year.22

§ Adjusted for baseline measures.

From: Higher HRU and Costs With Uncontrolled Epilepsy

Study Design: Retrospective, longitudinal, matched-cohort analysis.

Study Sample: US adults ≥18 years of age; 110,312 Medicaid population (matched cohorts, n=3454); 36,529 employer population (matched cohorts, n=602).

Limitations: Work-loss estimates based on subset of commercial claims, potential selection bias per group assignment, excluded less severe seizures, adjusted to 2009 dollars.

References

- Szaflarski, M. Social Determinants of health in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;41:283-289.

- England MJ, Liverman CT, Schultz AM, Strawbridge LM, eds. Epilepsy Across the Spectrum. Promoting Health and Understanding. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. The National Academies Press; 2012.

- Healthy People 2030. Social Determinants of Health. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social determinants of health. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health

- Szaflarski M, Wolfe JD, Tobias JGS, Mohamed I, Szaflarski JP. Poverty, insurance, and region as predictors of epilepsy treatment among US adults. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;107:107050.

- Nathan C, Gutierrez C. FACETS of health disparities in epilepsy surgery and gaps that need to be addressed. Neurology. 2018;8(4):340-345.

- Healthy People 2020. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health

- Rosendale N, Ostendorf T, Evans D, Weathers A, et al. American Academy of Neurology members’ preparedness to treat sexual and gender minorities. Neurology. 2019;93:159-166.

- Libby AM, Ghushchyan V, McQueen RB, Slejko JF, Bainbridge JL, Campbell JD. Economic differences in direct and indirect costs between people with epilepsy and without epilepsy. Med Care. 2012;50(11):928-933.

- Kobau R, Cui W, Kadima N, Zack MM, et al. Tracking psychosocial health in adults with epilepsy-Estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;41:66-73.

- Fraser RT, McMahon BT, Wiggins A, Clift A, Hunter-Banks S. Consideration in developing a specialized epilepsy employment program: a sponsor’s playbook. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;102:106698.

- Kalilani L, Faught E, Kim H, et al. 2019. Assessment and effect of a gap between new-onset epilepsy diagnosis and treatment in the US. Neurology. 2019;92:e2197-e2208.

- National Association of Epilepsy Centers. Find an Epilepsy Center. 2021. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://www.naec-epilepsy.org/about-epilepsy-centers/find-an-epilepsy-center/

- Doran E, Barron E, Healy L, O'Connor L, et al. Improving access to epilepsy care for homeless patients in the Dublin Inner City: a collaborative quality improvement project joining hospital and community care. BMJ Open Qual. 2021; 10(2): e001367.

- Cui W, Kobau R, Zack M, Helmers S, et al. Seizures in children and adolescents aged 6-17 years – United States, 2010-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(43):1209-14.

- America’s Health Rankings. Health Disparities Report 2021. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://assets.americashealthrankings.org/app/uploads/2021_ahr_health-disparities-comprehensive-report_final.pdf

- Thurman D, Kobau R, Luo Y, Helmers S, et al. Health-care access among adults with epilepsy: The U.S. National Health Interview Survey, 2010 and 2013. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;55:184-188.

- Chesaniuk M, Choi H, Wicks P, Stadler G. Perceived stigma and adherence in epilepsy: evidence for a link and mediating processes. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;41:227-231.

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. County Health Rankings Model. 2021. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/measures-data-sources/county-health-rankings-model

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. White Paper: Redefining Primary Care for the 21st Century. Accessed November 3, 2021. https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/tools/workforce-financing/white-paper.html#tab2

- Data on file. UCB Health Project HOPE and Trust. The Epilepsy Experience. 2014; Slides 3-7.

- Data on file. Optimizing Epilepsy Care. UCB Health. 2019; US-P-DA-EPI-1900014.

- Cramer JA, Zhixiao JW, Chang E, Powers A, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs in adults with stable and uncontrolled epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2014;31:356-362.

Social Stigma

1 in 3 students with epilepsy said that they had kept their epilepsy a secret because they did not want to be treated differently2

Lower levels of medication adherence and information retention are more common in those with a higher feeling of stigma18

The unpredictable nature of seizures, feelings of helplessness of those who witness them, and the ongoing misinformation about epilepsy have resulted in people with epilepsy being stigmatized and isolated2

Even when seizures are well controlled, internalized stigma can reduce quality of life2

Those living with epilepsy have a 2x higher rate of anxiety and depression9